21 November 2020

The story goes that all spiral* staircases in castles turn clockwise so that primarily right-handed defenders, fighting downwards, would have an advantage over attackers whose weapon would be impeded by the newel post. It is a particular favourite of tour guides, appears in castle guidebooks (Hodgson & Wise 2015, 46) and interpretation panels (for example at Arundel Castle, West Sussex), has been included in many popular texts (Mortimer 2009, 160), gets incorporated into television documentaries, is widely present in internet articles and is liberally recited by members of online discussion forums.

Of all the stories connected to mediaeval buildings this is perhaps the one that has been the most resilient. Unlike many other mediaeval tales that I have researched there does not seem to be a shred of truth behind it. For some folk this can be quite a controversial opinion. Attempting to gently puncture the swordsman theory of spiral staircases gets a lot of pushback online. One reason for this might be the frequency of its repetition by grandparents or parents to children. Whilst working at or visiting castles, I inevitably hear this occurring and it may be that this familial link creates a strong bond between the myth and its proponents.

Debunking the Myth

It is not the purpose of this blog post to outline all the evidence against the swordsman theory. That data appears in the third chapter of my book Historic Building Mythbusting. However, before looking in detail at how this myth developed it might be worth making seven broad points:

- The swordsman theory is predicated upon the belief that castles were intrinsically designed as military structures. Going back as far as the 1970s, and gaining widespread recognition in the 1990s, castle specialists have proposed that these buildings were primarily structures intended to be impressive theatrical backdrops for complex ceremonies relating to status and prestige. Secondly, they were lavish residences, and only finally was there some consideration of fortification – which was often symbolic and rather ineffective. This is not to say that castles could not be used in times of warfare – demonstrably they were – but such moments were vanishingly rare (Liddiard 2005, 6-11; Johnson 2002, xiii-xix; Coulson 1979, 74). You can read more about the functions of castles in Mediaeval Mythbusting Blog #20: What is a Castle?

- On the rare occasions that sieges did occur the chroniclers were keen to report them – disaster and death garnered readership in much the same way that it still does for modern media headline writers. Consequently, we know a fair bit about how sieges were ended, and it was never the desperate violent rout on the staircases that is so beloved of Hollywood films. The most common endings of sieges were starvation (Rochester, 1215; Kenilworth 1266), threats of punishment (Nottingham, 1194), bribery (Newark, 1218), blunders (Conwy 1401), or clever chicanery (Chateau Gaillard, 1204). If a rare siege resulted in fighting on the staircases then the game really was up.

- There would be a sheer impracticality inherent to fighting on staircases. The stair at Colchester is so wide – 5 metres in diameter – that it would not have impeded the swing of those travelling up or down the flight. Conversely, the stair in the great tower at Goodrich Castle has a claustrophobic diameter of just 0.7 metres. Such incredibly cramped spaces would not have allowed for the swinging of any weapons at all and, if fighting had ever occurred (which it didn’t), short thrusting weapons may have been more practical. There is also the possibility that an upwards attacker may have had the advantage due to the vulnerability of the legs and nether regions of the defender, plus the uncertainty of balance caused by leaning over to fight in a downwards direction.

- If staircases were genuinely engineered for military purposes, then we should always find that they turn clockwise. However, as scholars such as Neil Guy and Charles Ryder have demonstrated, there are a substantial minority of newels which turn anti-clockwise (approximately 30% of all surviving examples).

- Critics point out that anti-clockwise newels are far more prevalent in late mediaeval castles – a time when it is commonly (and wrongly) assumed that defence was less paramount. However, there are many examples of anti-clockwise staircases in castles that were built during periods of conquest and war in hotly disputed territories. In the eleventh century, two of William the Bastard’s conquest castles – Norwich and the Tower of London contain them. The following century buildings constructed during the period of the Anarchy, including Newark, have anti-clockwise newels. Meanwhile, examples built in the north at Helmsley and Richmond were vulnerable to Scottish incursions. During the thirteenth century conquest of Wales both Gilbert de Clare and Edward I patronised anti-clockwise newels in their castles at Caerphilly, Conwy, Beaumaris and Caernarfon.

- Critics also try to claim that left-handed staircases are evidence that their patrons – such as a the Kerrs of Ferniehirst Castle – were pre-dominantly left-handed. This is also a myth and has been examined in Mediaeval Mythbusting Blog #24: Left-handed Kerrs.

- The direction of a spiral staircase was an architectural decision, not a military one. The direction of the twist may be related to the practicality of carrying goods, the spatial considerations of access, or possibly even one-way systems of access. Ultimately, they were high status structures which allowed vertical movement between prestigious spaces in a castle. They are rarely found in lower status areas of castles, in civic defences or in the buildings of the militant orders. Spiral staircases in castles were intimately connected with access to the most prestigious spaces and were therefore a marker of status.

The Man Behind the Myth

Despite this, the swordsman theory is a vastly popular story – so much so that I wanted to try and trace its origins to better understand it. I began that task under the assumption that it would probably first crop up in the writings of either eighteenth century antiquarians or nineteenth century military historians. Castles were a fairly late addition to archaeological research and one of the very earliest people to look at this class of monument was the French architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc (1814-79). As a military engineer, who saw active service during the siege of Paris, he should have been well-placed to advance the swordsman theory. However, in a 43 page discussion on the subject Viollet-le-Duc concluded that spiral staircases were ‘only a means of reaching the upper floors of a dwelling.’

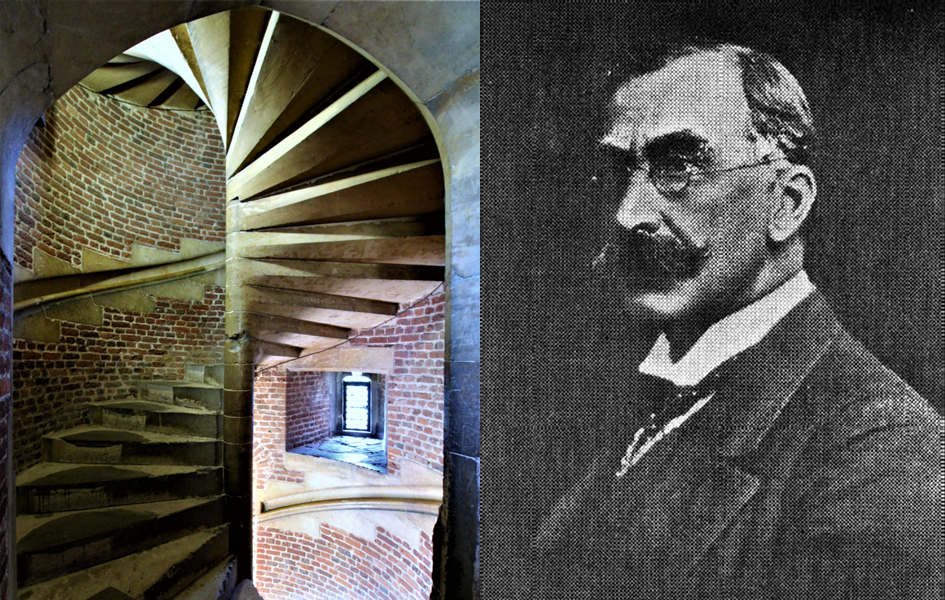

Instead, the earliest citation of the swordsman theory that I have been able to determine is in the writings of an English art critic by the name of Sir Theodore Andrea Cook (1867-1929). Cook first incorporated the story in his 1902 essay on spiral staircases entitled The Shell of Leonardo (Cook 1902, 106). This was then reprinted the following year as a chapter in his book Spirals in Nature and Art:

‘‘It is worth observing, however, at this stage of our inquiry, that while it was easier and more natural for a right-handed architect to draw plans for a staircase with a right-handed spiral, this “leiotropic” formation is not invariably better; for a man ascending it and turning perpetually to the left would always have his right hand free to attack the defenders, and the garrison coming down would expose their left hands on the outside.’

(Picture Source: Wikimedia Commons)

Cook ruminated that a right-handed architect would automatically wish to design an anti-clockwise stair so that the right hand would always be furthest away from the newel post whilst ascending. However, in his mind, this would have afforded a right-handed attacker the advantage over defenders who would find the swing of their weapons cramped. Correspondingly, his belief was that the designers of castles went against their natural instincts so as to facilitate a better defensive scheme.

Aspects of Cook’s life and interests may explain why he may have come to this conclusion. The subject matter of his 1903 book – spirals – immediately focused his mind towards staircases. His writing also betrays a powerful curiosity about which hand was favoured by significant individuals from both history and his own era. In particular, he was taken with the notion that left-handed people were excessively talented in their chosen fields including the Benjamite sling-shotters from the Bible, Leonardo da Vinci, Hans Holbein and the French Olympian fencers Lucien Mérignac and Alphonse Kirchhoffer.

The reason for his focus on these obscure French fencers is that he was himself a man absolutely obsessed with the sport. He set up the Oxford University Fencing Club in 1891, wrote a fencing column for the Daily Telegraph (under the pseudonym Old Blue), served on the committee of the Amateur Fencing Association (1904-1928) and the council of the British Olympic Association from 1905 until 1920. Given his triple interests in swordsmanship, the hand which men favoured and the bearing of a spiral’s turn, Cook was in a unique position to make a connection between the three. He may have been the first to offer an original explanation as to why most castle staircases turned in a clockwise direction.

If there is an earlier citation than Cook’s, then it failed to make an impact. Within a decade the writer Guy Cadogan Rothery (1912, 51-52) had repeated the swordsman theory and specifically referenced Cook in his bibliography. It was then absorbed into popular books on castles by the author Sidney Toy (1939, 208; 1954, 255) and by the mid-twentieth century it had become widespread accepted knowledge. This was no doubt helped along by famous on-screen portrayals of sword fights on spiral staircases including those in The Adventures of Robin Hood (1938) and The Princess Bride (1987).

Conclusions

As the origins of the story have been largely forgotten it still has many advocates. During January 2020 it was uncritically repeated by none other than English Heritage – the country’s foremost curator of mediaeval castles. However, of late, I have been heartened to see a fair number of people on the Medieval & Tudor Period Buildings Group discussion forum challenging repetitions of the myth. This can be contrasted with a prolonged debate on another forum – British Medieval History – just four years ago where I was very much a lone voice against the tide of the swordsman theory.

I do not doubt that the myth will continue to be recited, but its origins seem to be relatively recent – the probable source may have been the art critic and inveterate fencer Sir Theodore Andrea Cook.

* The actual shape described by such staircases is a helix. However, they are mostly referred to as spiral stairs so, for clarity, I have followed common English usage.

References

Cook, T. A., 1902, ‘The Shell of Leonardo’ in The Monthly Review Vol. VII No. 20.

Coulson, C., 1979, ‘Structural Symbolism in Medieval Castle Architecture’ in Journal of the British Archaeological Association Vol. 132.

Hodgson, T.& Wise, P., 2015, Colchester Castle – 2000 Years of History. Jarrold Publishing / Colchester Castle. Peterborough and Colchester.

Johnson, M., 2002, Behind the Castle Gate. Routledge. London.

Liddiard, R., 2005, Castles in Context. Windgatherer Press. Macclesfield.

Mortimer, I, 2009, The Time Traveller’s Guide to Medieval England. Vintage. London.

Rothery, G. C., 1912, Staircases and Garden Steps. T. Werner Laurie. London.

Toy, S., 1954, The Castles of Great Britain. Heinemann. Melbourne, London and Toronto.

Toy, S., 1939 (1985 edition), Castles: Their Construction and History. Dover Publications. New York.

About the author

James Wright is an award-winning buildings archaeologist. He has two decades professional experience of ferreting around in people’s cellars, hunting through their attics and digging up their gardens. He hopes to find meaningful truths about how ordinary and extraordinary folk lived their lives in the mediaeval period.

He welcomes respectful contact through email or on on Twitter, Instagram & Bluesky

The Mediaeval Mythbusting Blog is the basis of the book – Historic Building Mythbusting – Uncovering Folklore, History and Archaeology which was released via The History Press in June 2024. More information can be found here: